By Tav Nyong’o

Has incivility become the new obscenity?

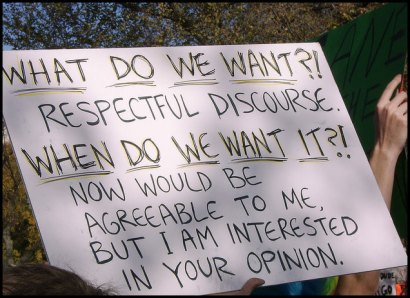

Everywhere one turns these days, it seems, ‘civility’ is being held up as a norm to which we all agreed to be held accountable. When was this consensus to be civil arrived at? Nobody can quite say. It must have been when we weren’t looking. But it’s suddenly everywhere: in open letters and videotaped homilies by university presidents, in the conference themes of progressive scholarly organizations, even in the campaign ads of Midwestern sheriffs (HT Ali Abunimah). Liberal icons John Stewart and Stephen Colbert even convened a national rally in 2010 “To Restore Sanity and/or Fear,” a sardonic retort to what those who attended perceived to be the raucous incivility of Tea Parties (HT Lisa Duggan). And indeed, civility sounds like a value all but a lunatic fringe should consent to. But it’s effects on our freedoms can be surprisingly negative. The exercise of what we could be forgiven for assuming were our “civil liberties” — freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, common use of public space — increasingly hit tripwire detectors for incivility, often with arbitrarily punitive consequences.

At the moment, the charge of incivility is most frequently being wielded against those whose political speech touches a third rail in American politics: the near-universal support our political class and academic leadership gives to the State of Israel. Steven Salaita, a scholar of indigenous resistance in Palestine and North America, lost a job at the University of Illinois when his righteous indignation, as expressed on social media, over the Israeli bombardment of Gaza this past summer offended some of the university’s donors and trustees. Civility here must be read as a barely veiled code for ‘civilized'; and this recourse to ‘civil’ as a standard to which all must adhere calls to mind Malcolm X’s famous critique of ‘civil rights’ as a limiting framework for the black freedom struggle. Malcolm implored black people to internationalize our struggle by refusing the US and state-centric model of “civil rights” under law and instead appealing to global solidarity with the oppressed through the rubric of “human rights.” It is precisely this global appeal to a planetary, anti-racist standard of human rights that led to Salaita being indicted for his “incivility,” transgressing the political quietism of the imperial university was enough to get him booted off campus without the pretense of due process.

Scathing, funny, and impassioned political speech did not originate on Twitter; our right to it is in fact the reason we have a First Amendment. But in the “incredibly shrinking public sphere,” as Lisa Duggan has termed it, declamatory speech of the kind that would not be out of place as at a campus rally is now occasion for professional reprisals, with even liberals handwringing over how to ‘tolerate’ the ‘intolerable.’

Ostensibly, the new civility codes have little to do directly with sex. But the neoliberal rhetoric of the campus as a space under threat is deeply intertwined with in the continued infantilization of the democratic sphere, and is thus deeply connected to moral and sex panics. Jennifer Doyle demonstrates this point in a powerful recent pamphlet, Campus Security. Doyle recounts how one police justification for the notorious pepper spray incident at the University of California was the need to protect students, gendered as feminized victims, from the masculinized and racialized threat of occupiers who weren’t currently enrolled students. The justification of the use of real force against students in order to protect them from hypothetical aggressions is the kind of security state doublespeak we routinely confront these days. At the University of Illinois, for example, it apparently fell to administrators, trustees and donors to protect students from the political viewpoints of prospective professors, when and where those views could be adjudged (unilaterally, without any grievance process) to create even a potential situation of harm, discomfort, or threat.

The imposition of civility comes at a curious juncture when privacy is also everywhere under assault. The appeal of civility for those who stand to be regulated by it is that it will provide shelter from the radical loss of privacy that new technologies are unleashing. As Mark Zuckerberg once retorted when challenged regarding insufficient privacy controls on Facebook: what’s the problem if you have nothing to hide? Similarly, those who defend civility as a standard assume that only the truly aberrant would have anything to say that couldn’t be expressed civilly anyway. And why would we want to extend them the protections enjoyed by others?

These protections ostensibly extended by the new civility, of course, fall unevenly on actual students and other young people. Civility failed to protect Michael Brown, due to begin classes at Vatterott College this fall, who was shot and killed by a police officer in Ferguson, Missouri while walking in his neighborhood. Immediately after his murder, he was retrospectively vilified as a dangerous hoodlum, not a recent high school graduate with no prior criminal record, much as Trayvon Martin and so many black women and men before and after him have had their histories, rather than those of their assailants, placed on public trial. When Brown’s community rose up in righteous indignation against police occupation, the black exercise of civil liberties was met with tear-gas, rubber bullets, agents provocateurs, tanks, snipers and police screaming “animals!” at the citizens they were sworn to protect and serve.

In the wake of Ferguson, many more Americans learned that “civility” is experienced by black Americans primarily as compulsory and non-reciprocal compliance to arbitrary state violence. There were many messages of solidarity, and practical exchanges of resistance tactics, between Gaza and Ferguson. But, despite these rhizomatic uprisings against antiblack racism, imperialism, and war — all of which challenge us to be radically critical of the promise of freedom, democracy and civil society dangled before us by our rulers — the answer in some quarters remains, stubbornly, more of the same. More civility, rather than a radical questioning of its terms.

In the wake of such brutal and total abrogation of basic constitutional protections, international human rights, and the rule of law in the summer of 2014, one must ask: what is the point of being civil? If civility means the censorship of intellectuals, deference to racist cops, complicity in our state’s funding and support of aerial bombardment of civilians, and acquiescence to a decayed and corrupt system of democracy-turned-plutocracy, of what value is civility, exactly? What alternative to it might there be?

For queer politics, Gayle Rubin’s foundational essay, “Thinking Sex,” holds enduring relevance on this score. Her ostensible topic in that essay is sex and pleasure, not suffering and violence. But everything that is at stake in the essay has to do with the ability of the state and media — and ourselves — to magically convert the former into the latter, and to cultivate moral panics around harms where there are none. Rubin argued that our inability to recognize and value the range and diversity of means through which we seek and obtain pleasure, our reluctance to take sex seriously, is intertwined with a more general logic of repression, exclusion and violence.

In order to challenge the logic of repressive tolerance that divides us into good, civil subjects and bad, disorderly ones, we cannot seek to rescue the most eligible of the socially stigmatized: those clearest to the center of what Rubin calls “the charmed circle.” We must directly confront the apparatuses that divide the acceptable from the unacceptable.

Rubin’s charmed circle resonates with an image Kimberlé Crenshaw turns to in her famous law review article that disseminated the concept of intersectionality. Here she compared antidiscrimination law reform to the effort to lift a group of individuals from a subterranean basement, and the temptation to start with those nearest to the top, those whose difference seems the easiest to rehabilitate. Intersectional analysis, in Crenshaw’s view, was the refusal to take this easy out, and to instead labor on working on injustice from the bottom up.

Whether from the outside in, or the bottom up, both Rubin and Crenshaw urged feminist, anti-racist, and queer organizing not to pick and choose those campaigns deemed most winnable, those victims deemed most telegenic, those tactics deemed most acceptable, or that language deemed most civil. I have to admit that this is a difficult standard to live up to. Particularly as the political center of the nation has drifted ever-rightward, as the scale of endemic crisis grows ever more planetary, one can plausibly wonder if principled radicalism grows self-canceling past a certain point. But there seems to be no way to ask this question without reinstating the hierarchies that Rubin, Crenshaw, and a host of other intellectuals and activists have urged us to dismantle. And so it seems we still desperately need more politically vital questions to ask and answer than the tired old saw of “where do you draw the line?”

The very drawing of the line, Stefano Harney and Fred Moten show in their powerful recent essay, The Undercommons, is a strategy of white settler colonial rule. “The settler,” they write, “having settled for politics, arms himself in the name of civilisation while critique initiates the self-defense of those who see hostility in the civil union on settlement and enclosure.” Politics casts itself as surrounded by the pre-political, the anti-political, the para- and the infra-human. Their radical critique of politics as we know it, in favor of social life as we feel, sense, think, study and celebrate it, points us beyond the stale coordinates offered up by yet another civics lesson delivered by our betters. We don’t need to learn to be better citizens; as the ongoing mobilization around the Salaita case, around Ferguson, and a series of other insurgent movements shows. We need learn how better to refuse the terms upon which citizenship and the good star of “civility” is offered, always provisionally, to the charmed few.

As commentators have noted, civility sounds like a venerable democratic principle, but is actually antithetical to the direct and participatory democracy many want to build. Democratic society — and in particular the social movements that push against the constraints of populist conformism — in principle relishes vibrant and vituperative antagonism. And yet one routinely encounters attempts (such as the recent NY Times opinion parsing an invidious distinction between ‘impoliteness,’ which may be acceptable, and ‘incivility,’ which is corrosive. The distinction, it turns out, is unworkable, begging the question: then why draw it?

Perhaps a more useful question than where to draw the line would be to ask: Why are we, who are cast outside the circle of privileges that accrue to the civilized, still drawn to and invested in the lure of civility? Is it precisely because we sense that it is a tape against which we are measured and forever falling short?

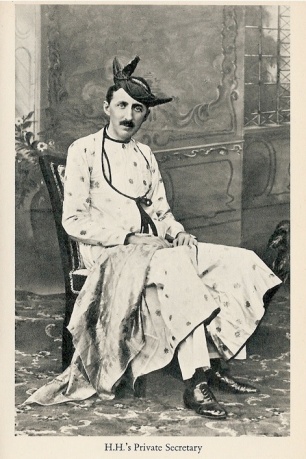

I learned this lesson early in life watching A Passage to India, a film that had an indelible impact on my postcolonial childhood in Kenya. Indeed, the film instilled in me the anticolonial Kenyan ideology that Dinesh D’Souza hilariously attributes to our current president (if only!). In the film, Dr. Aziz, an educated Indian doctor during the period of British colonial rule, struggles to balance his genial and tolerant nature with the constant racism and snobbery of his English “betters.” In one unforgettable scene, Aziz pretends to have a spare collar stud (whatever that is) to lend to the Englishman who is brashly getting dressed right in front of him, which Aziz has to discretely remove the stud from his own impeccable suit. Later on, another Englishman, the local magistrate, mocks Aziz for appearing in public “in his Sunday best” but forgetting his collar stud (whatever that is). He casts racist aspersions on the doctor for being a foolish colonial mimic: trying to approximate British civil standards only underscores how innately different he is.

The moral of the story for ten year old me was clear: a) these British colonialists are crazy and b) don’t ever assume that your efforts to live up to Euro-American arbitrary standards of civilized dress, deportment, or language will ever be enough to reverse the power imbalance.

I was too young on first watching A Passage to India, however, to truly grapple with the second half of the film, which turns darker when Ms. Quested, a visiting Englishwoman Dr. Aziz thought was a friend, accuses him of rape, prompting a dramatic trial which ends up putting the unjust colonial system of law in the docket, and sends Aziz bitterly fleeing from “civilized” English India. His personal effects are exhibited in court, he is accused of planning a trip to a brothel, and otherwise depicted as a sex-crazed savage, rather than a genteel, English speaking physician. At a climactic moment Ms. Quested withdraws her accusation (making this a tricky film to revisit in the current climate of victim-bashing, I well recognize), but the stakes in interpreting this outcome are not nearly so simple as racism versus sexism. The total abandonment of Ms. Quested by her white colonial society, once they cannot use her victimization as a legal cudgel against insurgent Indians, tells the viewer all she or he needs to know. The colonial state is both racist and sexist, even (or especially) when it is defending values such as civility, feminine virtue, rule of law and white supremacy.

In an earlier blog on this site, Jack Halberstam explored “how a neoliberal rhetoric of individual pain obscures the violent sources of social inequity” and argued that “neoliberalism precisely goes to work by psychologizing political difference, individualizing structural exclusions and mystifying political change.” Watching A Passage to India again today reminds me of the long colonial prehistory to contemporary neoliberalism. As many scholars in critical race studies have noted, colonized and racialized people were the first “flexible” and “precarious” subjects: that flexibility often demanded through the dynamics of what Homi Bhabha calls “sly civility.” Dr. Aziz, until his powerful rejection of the British at film’s end, embodies this sly civility: only when he grasps his fate is a collective one can he discard the exceptional status bequeathed him as one of the educated “good ones.”

In a contemporary context, Joseph Massad has recently written powerfully about how civility is used to police the boundaries between acceptable and unacceptable Arab- and Muslim-Americans, and how we ourselves can get caught up in those police actions. “The war to control the university rages on” he notes, “but the forces of repression, which hide behind white Protestant normative civility that they deploy to advance neoliberal control, are sharpening their knives and learning from their past mistakes.” Behind every document of civility, he might as well have continued, is a document of barbarism. Creative disobedience to compulsory civility isn’t any kind of guarantee. But without its wild resources we would be greatly impoverished to wage the kind of struggles we are in the midst of now.

![[singing+cats.jpg]](http://bullybloggers.files.wordpress.com/2014/11/a78c5-singing2bcats.jpg?w=323&h=229)